A 38-acre land donation to the Pennypack Trust brings with it tremendous promise, and a weighty sense of responsibility – By Chris Mendel, PLA, ASLA, Executive Director, Pennypack Ecological Restoration Trust

A 38-acre land donation to the Pennypack Trust brings with it tremendous promise, and a weighty sense of responsibility – By Chris Mendel, PLA, ASLA, Executive Director, Pennypack Ecological Restoration Trust

As political divides widen and headlines blare news of conflicts across the globe, it might seem as if civilization is cracked and may never heal. But perhaps lost in the maelstrom is the fact that human thoughtfulness and generosity are still amply demonstrated. As I stand with my foot on a mossy, fallen Red Oak, peering down into a glen in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania on a humid June morning, that reality could not be more tangible.

The land I’m gazing at spreads between Washington and Inverness Lanes and holds within it a pristine section of Terwood Run. White Oak, Red Oak, Beeches and other marvels stand here, towering at places well more than 100 feet in the air.

There is an inviting undulation to this landscape. It almost demands a hike! But not yet, not yet.

The reason I am in this privileged position, looking out on former farmland that has not been mowed, grazed or harrowed in well over a century, is due to the MacPhee family. Through their ethics, their passion for nature and history, and their thoughtfulness, the Pennypack Trust is now the grateful steward of 38 acres of woods and streams that we will tend and care for, in alignment with their wishes.

The task, in accepting this land, is not small and it will carry with it years of work and planning, sweat and worry, to be honest.

We’ll get to the work part, and there is a lot of it, but first, let me recount a story. As with any story, there are lost threads, striking turns of fate, and the narrative of how people lived, what they cared about, and how they wanted to be remembered.

A Profitable Lens

We don’t begin at the very beginning. But we do look back to Sansom Street in Philadelphia, where a wholesale lens grinding business was launched sometime in the 19th Century by the father of one Andrew Vinton Brown. The business thrived to the point that A.V. Brown, having inherited his father’s business, began to look beyond the family home on Tioga Street in North Philadelphia with dreams of establishing a country home. AVB was a stolid presence in social and business circles in Philadelphia. He was friends with the presidents of both the Reading and Pennsylvania Rail Roads, and a member of the Union League.

He was like many people of means, the Pitcairns are just one example, who identified the Huntingdon Valley, accessible by train and automobile, as the place to establish a gentleman’s farm. And he did exactly that, purchasing a 40-acre dairy farm in 1905 that we think dated back to the 1700’s.

Under his direction, his gentleman’s farm house was renovated over 6 years to entertain family and friends. It was said to contain 21 rooms, 6 bathrooms, and 8 fireplaces.

There was a music room, housing an organ, a grand piano and a harp. Can you imagine what notes may have emanated from that house in its glowing prime, plucked harp strings and tinkling piano chords blending in with the chirp of crickets and other outdoor creatures on balmy evenings?

There was a music room, housing an organ, a grand piano and a harp. Can you imagine what notes may have emanated from that house in its glowing prime, plucked harp strings and tinkling piano chords blending in with the chirp of crickets and other outdoor creatures on balmy evenings?

The grounds of the estate were carefully thought-out as both pleasure and production gardens. A trove of photos kept by AVB’s grandson, Alex Vinton MacPhee, shows that the Browns were passionate devotees of the outdoors.

Grand rose gardens, an exquisitely designed rectangular pond, large vegetable gardens, paddocks for swans and turkeys, and a carefully repeated theme of stone walls tied these outdoor spaces together into a grand estate. A full-time chauffeur, gardener, gamekeeper, and several house staff tended to the property through the 1950’s. As a trained landscape architect, the very idea of what was built here and how it ran gets my mind churning!

Domestic and wild animals are clearly something the family enjoyed having around. Turkeys, swans, ducks, chickens, peacocks, even raccoons were part of the landscape. Recalling aspects of his childhood, Alex said that “I’m not sure if it was more of a garden or a zoo.”

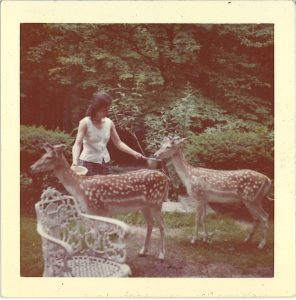

Clearly, though, the family shared and cultivated a commitment to and appreciation for animals. There’s one picture of a little boy (Alex) next to a deer, that begs explanation.

Now 84 years old, Alex remembers that a coal truck driver collided up north with a doe. Everyone knew that her fawn was doomed without a foster parent. AVB brought the fawn home the year Alex was born.

The estate’s game keeper raised “Flag” (so named after her tail waiving) in a spacious 10,000 square foot enclosure with a custom-built stall. While she’d escape periodically, she always came home, happy to get the attention she was given. Remarkably, Alex would grow up with Flag through his entire childhood. Flag died when he was 18.

Shifting Stones, Shifting Fates

Shifting Stones, Shifting Fates

As I look at Alex’s photo album, it’s the property’s water features that keep catching my landscape architect’s eye.

“The pond” as Alex calls it is acutely rectangular, set in local stone, and is the largest vessel in a series of spring-fed basins and runnels that originate nearer to Cold Spring Road. The stonework is still evident today, though it’s buried by an intimidating forest of bamboo.

I can still make out straight, parallel lines, semi-circular coves made to accommodate tree trunks, and a stone spring house. The water feature is just a part of the Vinton Brown’s and MacPhee’s indelible mark on this land. It’s another facet of their financial, architectural and philosophical legacy.

The pond was a focus from the back of the house, watched over from a sweeping back patio, and no doubt a tempting view from so many upstairs bedroom windows. This geometric water feature also conducted water across the landscape to a large production garden where most of the fruits and vegetable and cut flowers were grown.

Set on hill, the house enjoyed panoramic views across what is now the Trust’s Raytharn Farm. In photos a century old, the outline of what we now call Peak Woods is immediately clear to me and so are the spires of the Bryn Athyn Cathedral.

Oddly, a few photos of the interior of the newly completed cathedral are dispersed in the photo album; yet another indication that AVB and the Pitcairns were allies in this valley’s social fabric.

Oddly, a few photos of the interior of the newly completed cathedral are dispersed in the photo album; yet another indication that AVB and the Pitcairns were allies in this valley’s social fabric.

What strikes me and what I think is notable is that the house sits high on the landscape but not dead center on the property. The house and its blend of manicured and production gardens and out-buildings are all concentrated in a quarter of the land. The rest is natural and largely forested.

Slopes release to a creek kept cold by the shade of mature trees. Aerial photos from 1942 confirm that most of the property was a patchwork of mature forest. Any agriculture that went on prior to when the Vinton Browns landed here had run its own course at least 50 years before.

AVB enjoyed this place for many decades and left this life in 1948. The estate then became the full-time home of his wife Ida. She lived alone among so many empty bedrooms, aided by her butler and cook, until she passed away in 1959.

“I thought that house was one of the most fascinating places in the world,” Alex told me.

“But it was too much for my dad and my sister to keep up. Raccoons punched a hole in the roof. The Township told my sister ‘fix it up or take it down’.” So Margaret had the house dropped into its foundation in 1985.

But life continued for the land and the family. AVB and Ida’s daughter Helene Vinton Brown and her husband Alexander Anderson MacPhee live just down the path with their son Alex and daughter Margaret. Helene and Alexander raised their family in a house built as their wedding present. It’s still standing and in fine shape just off of Washington Lane. One of our staff will live there soon.

Alex MacPhee had wealth in his pedigree, but he, like so many of us, had to work for his bread. He tells stories of being laid off from Republic Steel and Bethlehem Steel. Alex and his wife Conchita both worked, Alex improvised as a physics teacher and auto mechanic. They have vivid memories of lean times and chasing work in the region, from in Buffalo, NY to Allentown, PA, and finally back home.

Holding a Legacy in Trust

Nearly 120 years since his grandfather first took ownership, Alex and Conchita live at the opposite corner from his boyhood home at Inverness and Terwood in what was originally built as AVB’s Chauffeur’s house. Alex and Conchita have been married for 63 years. They earned the funds for their retirement by starting and running their own business, a geotechnical service. They raised one boy and two girls, all of whom live elsewhere now with families of their own.

Margaret, Alex’s sister, remained in the house off of Washington Lane until the 1990’s. She was a staunch lover of animals. She raised injured animals and fed the wild ones daily. Margaret, who never had kids, cared deeply for the land and environment. Her will is a testament to her and her family’s values.

Sister and brother, Margret and Alex are the third generation to own and live on the land, all of whom were animal lovers. Independently they each continued a tradition of taking special care of wild animals, leaving food out for a variety of birds and mammals.

As I sat with Alex and Conchita on a recent late winter afternoon, turkeys wandered just outside the living room windows and deer ambled near the kitchen nook. All were comfortable in their trust of Alex and Conchita, and in the decades-long knowledge that this was one family that would see that food was placed outside for them daily.

The landscape has undergone enormous change in that span of Vinton Brown/MacPhee ownership. It’s moved from production farm, to pleasure gardens, and then ever-so-slowly transformed to a naturalized state.

At no point did any Vinton Brown or MacPhee ever consider that this land should be subdivided and developed. No one felt the need to “cash out”. We all owe a sincere debt of gratitude to the three generations of Browns and MacPhees who protected this land. Margaret Vinton MacPhee in particular needs to be thanked for ensuring that her land would be protected after her passing.

The details of her will reveal the depths to which protecting nature was her highest priority. She clearly knew that people were the great disrupters of nature. Her will states that the land will be kept in a natural state and should be used as an arboretum and wildlife sanctuary.

The details of her will reveal the depths to which protecting nature was her highest priority. She clearly knew that people were the great disrupters of nature. Her will states that the land will be kept in a natural state and should be used as an arboretum and wildlife sanctuary.

Visitors would be allowed only from April to October, limited to a maximum of 10 people per day, and only between the hours of 9 am and 3 pm. If you were one of those lucky 10 visitors, there were to be no benches, no water fountains, no trail even! These rules circumscribe Margaret’s knowledge that dawn, dusk, and nighttime were vitally important to wildlife. Furthermore, she wrote “adequate feed is to be left out for the wildlife on a regular basis.”

These and other matters expressed in her will required adjudication from the Attorney General’s Office and the County’s Orphans’ Court. The Pennypack Trust provided a detailed plan that would respect Margaret’s intent to the fullest extent practicable. The Orphans’ Court of Montgomery County adjudicated in favor of the Pennypack Trust taking ownership since the Will of the late Margret MacPhee could not be fulfilled as written.

Trails, for example, when properly designed and maintained, are indispensable to the sustainable management of an urban forest, protecting the forest by limiting and mitigating human disturbance and guiding people around or away from sensitive habitats.

Feeding wildlife is simply illegal as it builds unhealthy dependencies upon humans and often leads to the spread of communicable diseases among wildlife. The Pennypack Trust is honored to be the next and permanent caretakers of this land and will name the parcels the Margret MacPhee Wildlife Sanctuary at the Pennypack Trust.

The Work at Hand

What was the last occupation of the site? What did the “hey day” of the estate look like? How did the farm before it grow and decline? How was it managed?

These are questions that most folks find endlessly fascinating. Because we are a land trust and nature preserve with the term ecological restoration in our name, we find these questions important, too. But, through an ecological lens, these transitions from agriculture to manicured gardens are each forms of disturbance.

What’s abundantly clear in the vine tangled naturalized landscape we see today are the very loud echoes of the garden genres. For instance, the central agricultural and production garden site was tended for the last time in the early 1990s. In those active decades, soil was tilled, fertilizers added, decorative plants, vegetables, cover crops, all of these were rotated and renewed annually. But today more than 30 years on, the site is covered in a low mat of multiflora rose and porcelain berry. Not a single tree dares to grow there as if in an eerie homage to the gardens of long ago.

Along the boundary of the former Cold Spring Road, several varieties of bamboo were used as a privacy hedge. Decades later that bamboo has grown as we know bamboo will, spanning acres of land, completely enveloping those exquisite water features. It will cost many thousands of dollars to remove (or at least control) those bamboo soldiers over the next several years.

The impact of feeding deer for so many years is also clear to the trained eye. The forest floor is dominated by plants that deer won’t consume: stinging nettle, poke weed, Japanese stilt grass, barberry, and poison ivy are all that prosper in the dappled shade.

Most n otably, there is zero natural regeneration of the mature beeches, oaks, maples, and hickories that still make up the canopy. Whatever seedlings that grow from them become food for the population of deer that feeding attracts. As a consequence, damaging events like straight-line winds and tornados created wounds in the canopy that can’t heal. Only invasives like Devils Walking Stick and Tree of Heaven poke up into the sunlit gaps.

otably, there is zero natural regeneration of the mature beeches, oaks, maples, and hickories that still make up the canopy. Whatever seedlings that grow from them become food for the population of deer that feeding attracts. As a consequence, damaging events like straight-line winds and tornados created wounds in the canopy that can’t heal. Only invasives like Devils Walking Stick and Tree of Heaven poke up into the sunlit gaps.

So what will restoration look like, bracketed as it is by family wishes that must be respected, a well- entrenched enemy of invasives, and the limited resources of the Pennypack Trust?

I can tell you for certain that we will not rush to any conclusions. We will not force this place into a costume of current trends in restoration discussed at conferences. We will not clear-cut or uniformly spray with herbicide.

Rather, our plans must start by acknowledging that our most important asset is time; our weakness is our limited staff size, so whatever action we take must be patient, well-measured, and robustly planned.

We’ve done this before, in fact we do it incrementally every year. We take back a small piece of disturbed ground from invasives, we plant it according to the needs of food chains, plant communities and climate, and we mind it, year after year.

Where deer would consume the next generation of trees and shrubs, we plant them, protect them, and train volunteers to watch over them. Will the MacPhee Wildlife Sanctuary look like the grasslands we planted across the street or the woodlands we manage elsewhere? Maybe not.

Maybe we need to pick a different successional stage from which this forest can resprout. Maybe the thing most worthy of protection isn’t the remnant forest, but Terwood Run which is still (amazingly) connected to its floodplain and rich wetlands. Whatever the plan entails, this restoration effort will tax our staff with ever-increasing acreage to plan for, execute, maintain, and monitor. While the land is truly a gift, the work of guiding it will always be demanding.

Our job is to manage these lands as a network of habitats. The MacPhee parcels have always played a significant role in the wildlife that the Pennypack Trust has hosted. Animals have moved freely through the MacPhee’s property for a long time, well before the Pennypack Trust or the Watershed Association even existed.

Very quietly, almost unknown to the public, the protective instincts of the Vinton Browns and MacPhees have been a benefit for Huntingdon Valley. We should all be amazed at their selflessness, at their disregard for the lure of easy money in land development, and their vision to see the land not as their own, but as an irreplaceable resource that requires constant watch, love, and respect. Now it is our job, as a community of conservationists, volunteers, and neighbors, to continue their tradition.

This is not a responsibility we take lightly. And it will take resources to do this job properly. But let’s take this moment to take a breath, wonder at this wonderful opportunity, and appreciate the family that made this possible. This is the stuff that holds us together.